The top 3 principles of sustainable economics

These are three important and exciting topics in sustainable economics. These are concepts that are gaining a lot of traction and idea we can expect to hear more of. The top 3 principles of sustainable economics I’ll talk about here are:

- Localised economies

- Assigning a price to priceless things

- Reuse and recycled economies

Localised economics

Localised economics is the opposite approach to the ‘decentralisation’, ‘privatisation’ and ‘financialisation’ we see today. What does this mean? It says to spend money locally to boost local business and keep the profit and value from the economy. Spending locally supports income for people in communities rather than increasing revenue for the ultra-rich and their lawyers working on wealth extraction schemes. It goes back to an old model of economics that exists for countries undergoing development. Only here its for communities undergoing economic development.

Far too often, the appearance of multinational chains on high streets indicates that money is being transferred out of the people’s pockets and into the corporations. The corporations do not have loyalty to any particular area. They will hire staff from anywhere and build their business anywhere. Supporting them does not necessarily create an economic boost in the local area. Local companies, however, will serve locals and will be directly influenced by the trends in what local people want to see. They will also pay local taxes. Generally, local businesses will support local community economies.

Some exciting schemes encourage this type of local economy around the world. For example, in Bristol, where I live, there is a bristol pound- a local currency that you can only spend in local shops. It’s not recognised and distributed by the Bank of England; you just use it to support local shops in the city. You can spend the Bristol pound in independent shops, on some busses and local services like that. This site explains the goals and the importance and benefits of spending locally.

Assigning correct prices to priceless things

At the moment, we know that there is an economic value to the wood from 100 trees, but there is no monetary cost of the atmospheric loss of cutting down those trees. However, there is no environmental cost to burning those trees for heat, even though it actively damages the atmosphere, devaluing its protection of all life on earth. There is no economic cost to the beauty of the landscape and the habitat that exists around those trees.

The way our economy values things is straightforward. While it works for the global markets, we all intuitively know there’s a greater value to the atmosphere and planetary biodiversity.

The mismatch between what we instinctively value and what financial evaluations tell us is valuable creates this strange economy that acts against what makes humans thrive.

So this economic principle suggests we assign values to the natural world. In doing this, the benefits and costsof all our activities can be fairly assigned.

Assigning costs is like creating value in the ‘commons’ (the part of the world we all jointly own and share). Global government bodies could assign common values to our natural commodities. In fact, there are fascinating ideas of how this could work and who would create and sustain the value of the natural world.

Re-use and recycled economics

We know that re-use and recycling is important. But there are limits to what recycling can do; recycling always degrades materials. They can’t be used infinitely, only a few more times than otherwise, at the cost of an energy intensive process.

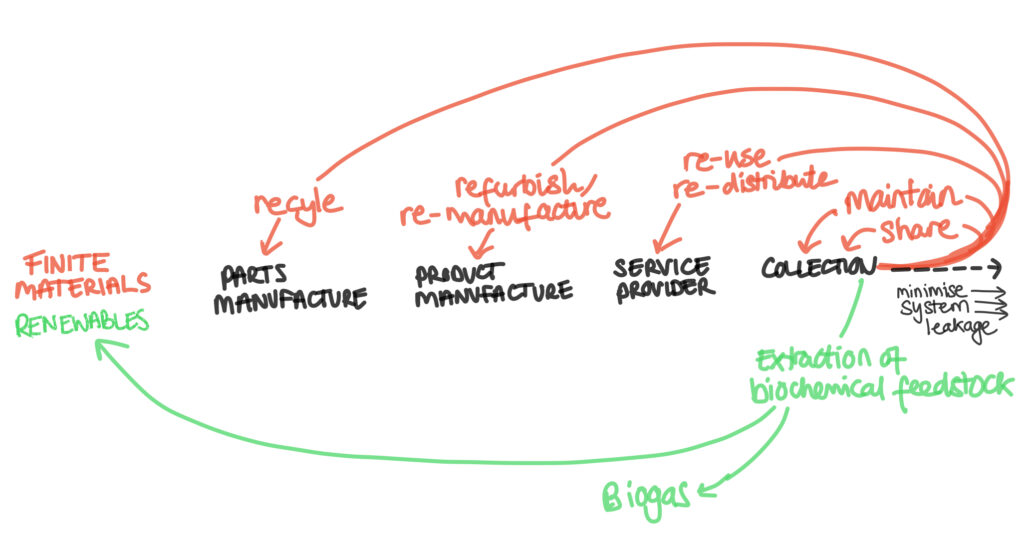

On an even bigger scale than re-cycling materials is completely redesigning how products are engineered in order to support a material leasing economy. The engineering system of products would change. Rather than buying a product and owning the materials in the product, you’d buy a product, and once you’d were finished with it, it would be collected. Companies would re-use them in future versions of the same product. These principles are part of what is known as the circular economy.

How could this work?

A lot of what we use material-wise is on a one-way trajectory. We buy a toaster, and there are loads of electronic components inside. Same for any battery divide in your home. But when we’re done with them, we throw them away. None of those devices are recovered. Companies extracted those materials from the earth for use in your toaster’s electronics. Most electronic components include some rare earth metals. They are finite resources on our planet and are complex and energy-intensive to extract. Therefore, no matter if you have owned your device for 5 or 10 years, it’s a short period in the lifecycle of those materials. And using these valuable materials so haphazardly is wasteful.

That is why economies of material lease and re-use could be great in sustainable economic development. Rather than the manufacturer of the toaster buying the material and accepting that once the device is gone, it’s gone, the manufacturer could lease the material from a material recycling company. Additionally, the toaster could be designed so that all the components can be taken out and re-used in the next generation toaster. We could design the metals as standard parts like screws, for instance. If materials are leased, not bought, there is an incentive to use them well, design for maximum efficiency and offer incentives to fix and recycle- better for everyone.

Top 3 principles of sustainable economics

This post looked at the top 3 principles of sustainable economics; localised economies, the pricing of priceless things and reuse and recycle economies. It’s important to remember the main issues and keep track of what is real and what is most important.

There is a lot of ‘business talk’ about corporate social responsibility and corporate sustainability. These topics are often greenwashed, which means they make surface-level contributions. Often carbon footprint measurements exclude some of the most significant sources of greenhouse gas emissions. Thereby, companies gloss over what is important without digging deeper into sustainable environmental protection and protection of natural resources.

If you’ve enjoyed this post, you may also enjoy this keystone post of mine:

What is sustainable economics? Where I talk about the Brundtland report definition, the sustainable development goals and some key economics concepts, including the three pillars of sustainability, the circular economy and Kate Rayworth’s economic doughnut.

I also have these other posts on economics: