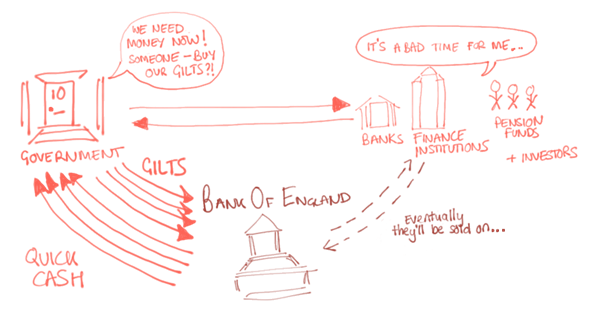

The government usually don’t really borrow money when they say they do… what they do is actually more like creating more money in a special scheme with the national bank (the Bank of England). It’s different because they’re not borrowing ‘from’ anyone, as the word ‘borrow’ might make us believe. They’re creating value and selling it. The buyers are the lenders of the money they make in those sales. This post in about how governments borrow money and who they’re borrowing from.

The bank issues ‘bonds’ called ‘gilts’. These are like little vouchers. The money the government gets for selling the vouchers is cash they can use to spend (on whatever they do to boost the economy). This is the money they have borrowed. They are borrowing it from the people or companies who have bought the vouchers. The vouchers are like a trust deal. The government can use their money for the time being in exchange for small interest payments. The vouchers sometimes have different forms, sometimes they are 5 year vouchers….sometimes much longer or indefinite.

Why is this good for the government?

They can, on the spot, sell these vouchers they create and immediately get a lot more money.

Why is this good for the ‘buyer’?

People with money need to put it somewhere. They’ll want to put it somewhere they’ll get interest from it so that it gains value over time. Government bonds give better interest than banks while still being low risk investments (compared with the other option which would be investing in the stock market).

Is this what the government does in a financial crisis?

What I’ve described until now is what happens very often. A crash is a particularly extreme case where the governments need to sell a lot of gilts all at once (for example £262bn worth in the early stages of the pandemic 2020). They also urgently need people and companies to spend money to keep the economy flowing as much as possible. The problem is that in crisis times, people don’t exactly have excess money they will want to be tying up in investments. So to help, the central Bank will often step in and buy up most of the gilts. They have the power to invent the money they spend buying the gilts.

In October 2020, the government had sold gilts worth £262bn to pay for their economic packages to help people through the pandemic (that’s effectively £262bn of borrowed cash) and of that amount, £246bn had been bought by the bank of England.(This is money article: Source here).

How/Why exactly are the Bank of England involved?

Why do the government issue gilts for the banks of England to invent money to buy rather than just inventing the money themselves? Great question. It’s about keeping up appearances of ’trustworthiness’. Since so much trade happens on speculation, the international credit rating of a country is extremely important. Not all countries can do what I’ve just described if there is no trust that their government is stable. So when the Bank of England buys the gilts they’re not officially buying them permanently. They’re buying them quickly and making a lose promise that they ‘will sell them into the private sector eventually’. This doesn’t always happen, but the ‘story’ told is: ‘the private sector is interested in buying government debt (because it will be profitable)’ which is good for the country’s credit rating.

The government does not want to be seen inventing new money for free. (Inventing money is called ‘monetising public debt’ or sometimes people say ‘printing money’ even though they’re not physically printing anything). This is traditionally seen as something that weak economies do– not “strong/well established” ones like the UK. In times of crisis, selling a ‘voucher’ (gilt) is a way they can sneakily get themselves cash while still technically selling it to the private sector (with the central bank as a middle man).

Don’t they eventually have to pay it all back?

This is all very well as a quick fix but don’t the government eventually have to give back the money they’ve borrowed when the vouchers end? After all people aren’t giving the government money, they’re swapping money now for money+interest in the future!

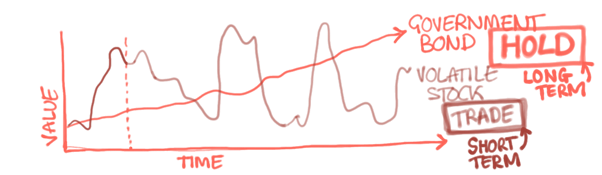

Well, although this is technically true, actually, they don’t really have to give the money back because they are sold as products which are ‘held’ not ‘traded’. Government bonds are low risk, low return investments. They are bought as the stable constant baseline. They are bought for the guaranteed interest payments rather than a quick win which you’d want to sell before value drops (as someone might do with technology stocks). For example they are often bought by big pension houses. These pots of money are left to grow steadily over the long term and the way they grow is the accumulating guaranteed interest payments which compounds over time. As you can see in this picture below, it doesn’t make sense to buy and sell bond all the time. They are long term investments- only worth their while over many years.

Don’t the interest payments push the government into more and more debt?

Yes. When the borrowing rate is low (as it usually is in a crisis) it doesn’t really matter because interest payments are generally low. Having too much debt is a risk for the government if/when interest rates rise. It’s not a short term problem but it is a bigger problem in the medium term. After a big crisis governments will try to reduce some of their debt by spending less than they earn through taxes. They can either raise taxes for people/goods or corporations or they can cut spending to do so. Extreme spending cuts are called austerity which was a really popular economic policy after the 2008 financial crisis. There are other ways they can do this (which will be the subject for a different post).

So to sum up what we’ve described here: When governments borrow money they’re not borrowing from another country. They are selling their debt in the form of little vouchers. These vouchers are bought either by the Bank of England or by big companies like pension houses whose strategy is to keep the bonds forever because they use the interest payments in their financial planning, not the capital. In that way, the government is theoretically in debt, but it’s not a debt that will ever need squaring up. Often this debt will be written off (which I explain in a post called QE). This is how strong/trustworthy economies deal with government debt. For weaker economies, this isn’t always an option, especially when there is no demand for the vouchers. In these cases, governments borrow money from other countries, but that’s the subject for another post.

Thanks for reading this post about how governments borrow money!

Please get in touch or comment below. I am a brand new blog and would love to hear your thoughts. New posts every Tuesday at 11am London time (BST)!