Welcome to this second post on the theories of the invisible hand and free market economies.

This post explores a key concept of economics: the market is most efficient when it’s left to do its things without regulation. Now here is that explanation in story form to bring it to life. Here you see a market working in action- this is like a micro-example of how our economy works and this is where we can introduce key works like ‘inflation’ and things.

Is it a real example?

Yes! These were real observations made by the American economist Richard A Radford on how free market economies emerged in war camps.

Who was he?

He had been studying economics in Cambridge when the war began and decided to join the british army. In 1942 he was captured and he spent the next 3 year in a Prisoner of War (POW) camp in Bavaria, in Germany.

How markets works: A story of prisoners of war

The set up

During the second world war in Germany, ‘enemies’ of the German state (this included Brits, French, Americans etc) were taken into war prisons where they were held captive. Many nationalities were grouped together in prison-like accommodation and organizations like the red cross would send them relief packages with some essential basic supplies including; tea, coffee, biscuits, cigarettes and soap etc. Every prisoner got the same as each other; the same amount of cigarettes, the same amount of tea and biscuits.

Despite having the same amount of items, the value of the items was different to different groups of prisoners. The Brits for example, valued tea more highly than coffee. Their neighbours, the french, valued the coffee more highly than tea.

A market economy begins to emerge

Some of the prisoners set up schemes to profit from these differences. Imagine each prisoner got 10g of tea and 10g of coffee. Some clever business men would go to the English and offer them 4g of tea for 5g of their coffee. Good deal for the English- they didn’t like the coffee anyway but they got 4 grams of extra tea! The business men would then go back to the French men and sell them the 4g of coffee for 5g of tea. Again, good deal for the French, the tea had little value to them but they were able to exchange for coffee; far more delicious! And the business men, each time they’re making a 1g profit and they can use the extra tea or coffee to trade with the Spanish or the Russians for whatever they may like; chocolate/ biscuits/ cigarettes.

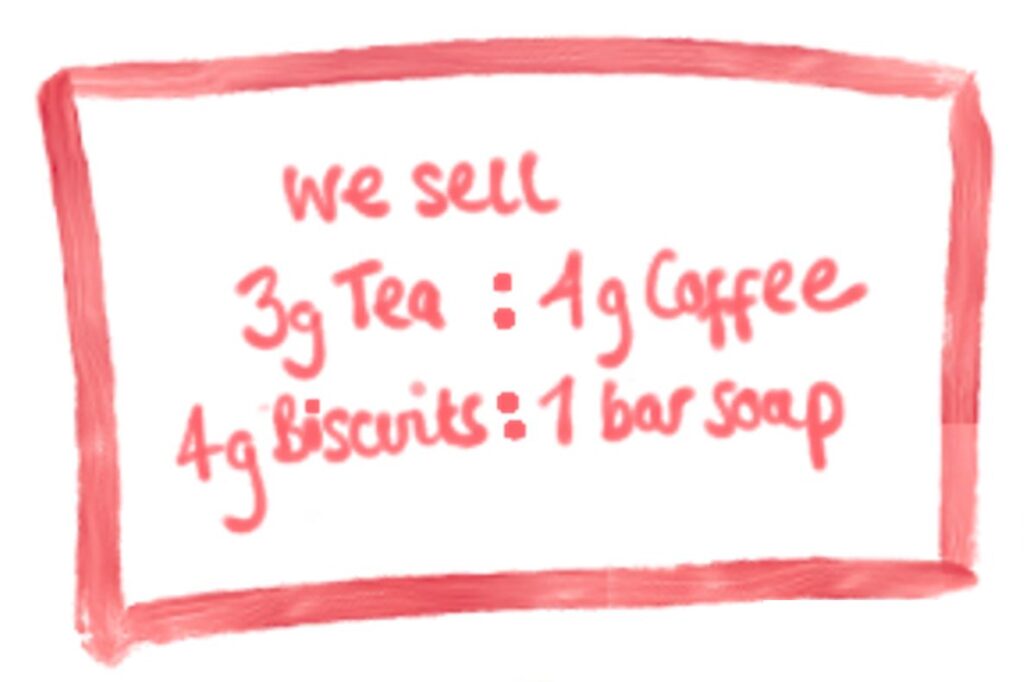

Every item in the camps had a value and the values of these items relative to each other became established. The English block set their prices, and each other group set theirs. Each block named the trades they were offering that day and pinned it to the outside of their block.

A more complex market economy takes shape

A complex web of trades began to take place and since every man was shopping in his best interest, he would seek out the best price for his trade from all the offers. For example a french man may have set his tea to coffee ratio as 1g tea for 5g coffee. If an English man fancied some tea but did not like the rate the frenchmen have set, he might offer an American 3g of coffee for one gram of tea. The american may himself not care for coffee but might happen to know that the Russians were offering one cigarette for 3g of coffee. So, being keen for the cigarette, that would have been a good trade for the American. In this transaction the French man’s initial offering would be undercut and he’d have to lower his prices to trade.

Eventually a stable set of prices and values was established and each prisoner began to understand the relative value of all their items. This is a mini market economy.

(made up numbers though!)

A currency emerges

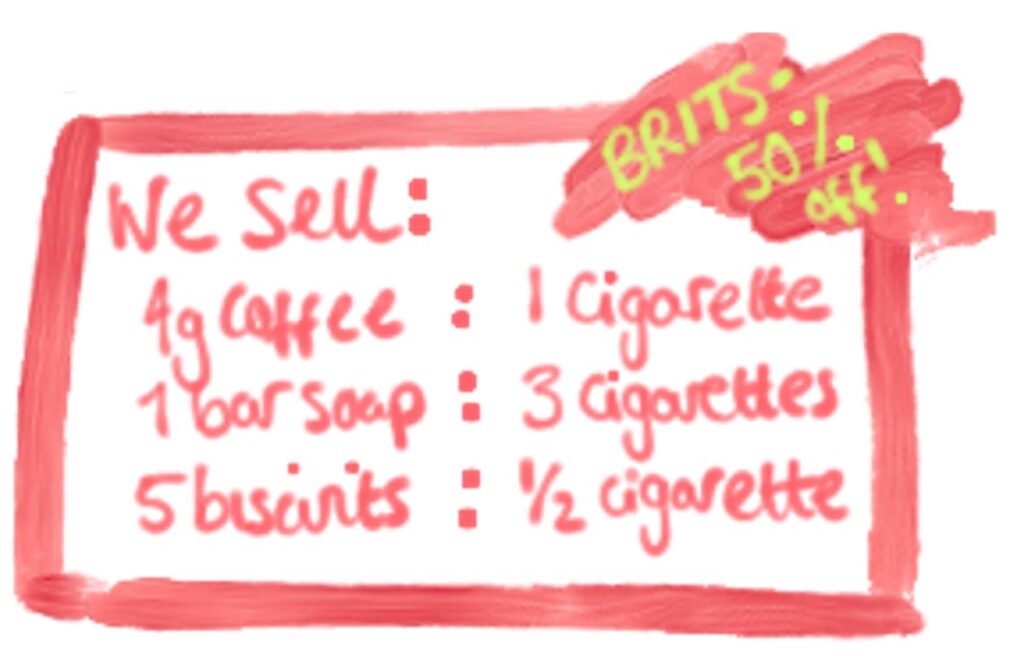

Rather than each unit listing the value of each item relative to each other item, cigarettes became the universal currency. Cigarettes were good because they were valuable to everyone, not perishable and they could be traded in half, quarter or even smaller quantities.

Even though the relative values of the goods was well established, this little inside economy experienced changes as a result of what was happening in the outside world. Some prices of some items were more volatile than others. For example, imagine food items- they were essential and so people would always need to buy them. However, there were some luxuries such as sugar/treacle. During times when the war was going well and the Red Cross had good access to the prisons, they could deliver generous amounts of supplies. The prisoners knew that their packages would be generous and would be arriving weekly. Knowing that their essentials would be coming, prisoners might save some cigarettes for safety, but they could also afford to spend a bit more on luxuries such as sugar.

So while the packages were generous, there was a lot of trade. This created the opportunity for entrepreneurial prisoners to open small businesses.

Business booms

Since there was money and trades flowing, some prisoners may have set up shirt washing services. Having paid for the food and everything they needed, prisoners in these good times might have had spare currency to treat themselves to a clean shirt.

Other businessmen set up coffee shops or even mini restaurants. Prisoners could pay the best coffee brewer for a cup of superior coffee rather than having to brew it themselves. (maybe this is a bit of a fancy example. I actually have no idea what sort of coffee brewing equipment they had but you get the idea!). The brewer might do so well that he could afford to hire more staff, a business accountant. He could even hire a chef and open a little cafe/restaurant. Since there was ‘money’ (cigarette currency) around, services could be expensive. There was always ‘plenty’. Even if someone spent all the money they had for the week, they knew more goods would come the next week.

Good times led to inflation…

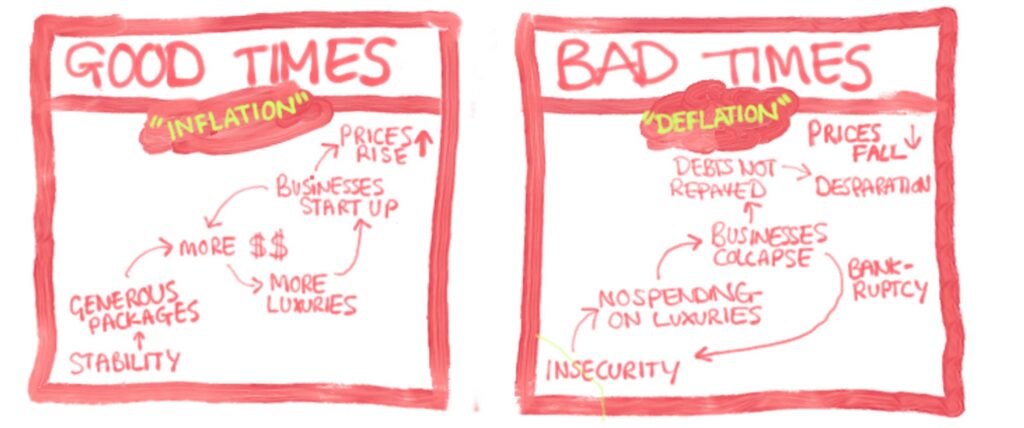

This security in supply also enabled long term loans to happen. People would lend money for a small profit or interest payments. They did it because they knew there was enough demand that a business could easily recoup investments. This security allowed even more businesses to spring up. The more businesses, the more money flowing around for spending. Prices could be set higher as there was so much disposable income. The economic word for this is inflation. It signifies rising prices when the times are affluent and the future (in this case of continuous generous packages) is secure.

What happened in bad economic times?

It was a war and there were, of course, also bad times. The cigarette currency was interesting because cigarettes grew to have ‘use’ value (as in they had value to smokers) and exchange value (they had value to everyone because they could be exchanged for anything). During the 5 years of war, there were occasional bombing raids very near to where the prison camps were. The red cross bases might be hit, or their transport routes might be disrupted. During long nights of endless bobbing raids, high anxiety led to prisoners smoking for far more cigarettes than normal. In the morning, when the raid finished, there was suddenly a lot less money (cigarettes) in the camp.

Although in good times, the prisoners might buy sugar and buy a ready made coffee from the cafe, now they would not buy themselves those luxuries. With less currency around, and without the promise of a generous aid package, prisoners might stash cigarettes and save them for the absolute essentials (like food).

Deflation in the market economy…

Prisoners who had some luxuries like sugar in their stashes (and might have spent 3 cigarettes on buying it) would try to sell it quickly to get much more valuable cigarettes which they could use to buy food. But no one would want the sugar now for the price of 3 cigarettes! It wasn’t worth it when they all faced hunger. Some of the ‘richer’ people might still fancy a bit of sugar. Since sugar holders were desperate to sell, rich prisoners could negotiate the price down from 3 cigarettes to just 1. Prices of everything in the trade web would fall– in our modern economy this is called deflation.

The cafe owner may have taken out loans to afford the stocks of coffee he needed. Suddenly, with no customers, his business would go bankrupt. Everyone he owed money to wouldn’t get their repayment and in an instant- they would all also be ‘poor’. Anyone else involved in any sort of trade with any of these people would also suddenly fall ‘poor’. This led to many prisoners facing prison bankruptcy (no food or cigarettes at all).

Overview…

The prosperous/affluent times are reinforcing positive cycles where riches are made by everyone. Those who started with a bit more or who opened businesses became particularly affluent as they could profit off the others. When the market economy was subject to bad and unstable times, many people went out of business. Many loans could not be repaid which meant that a lot of people become poor. These cycles are what is experienced in the modern economy today as well!

****************************************************************************************

Back to the blog post

I LOVE this example, it made the whole process of markets interacting so clear to me- and I love to picture a real example for any theory! I first read about this in a book called ‘Talking to my daughter about the economy’, by Yannis Varoufakis. The actual paper where Redford wrote about the market economy set ups in the POW camps is on google here. It’s a pretty easy read and gives loads more detail than I have and includes some really interesting mini stories about how people struck deals and made business within these camp economies.

The next few posts are about our economy, economic cycles, capitalism and growth.

Keep tuned and as always I’d love to connect with you- send me a message in the contact area to say hi!