Decarbonisation is complex because it involves a complete overhaul of the current systems we interact with. This means that as well as technology that needs improving and politics and law that needs bringing in, there are also social barriers to decarbonisation. This post explores human and social barriers to decarbonization.

This post includes racist cars, solar panels mis-used as tumble driers and spiritual energy customs.

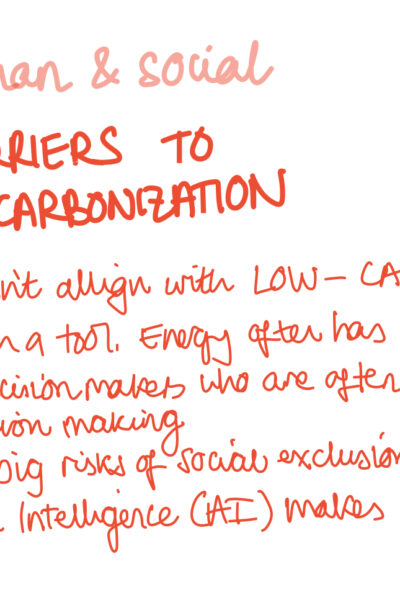

There are 5 main social barriers to decarbonisation:

- Human behaviour does not align with low-carbon behaviour

- Energy also has an (often overlooked) cultural value

- Decision-makers are distant which causes distrust

- There are big risks of social exclusions

- Artificial intelligence makes unacceptable social calls

Human behaviour does not align with low-carbon behaviour

The way we live is very different across countries and cultures, so designing a one-fits-all energy approach doesn’t always work. The difference in how humans interact and use energy creates a bottleneck in efficient design. In the portal, a macho culture means drivers rev their engineers harder and faster than in the UK. Typical Japanese homes aren’t heated very much, but families use lots of hot water for bathing and cleaning purposes. In Scandinavia, whole homes are heated, not just occupied rooms, as is more common in the UK. However, hot water use in Europe is generally lower than in Japan.

There’s another barrier to how we react to new things. To decarbonise the planet, we need a roll-out of electric vehicles; these are the current best solution we have to petrol and diesel. However, it’s tough to anticipate how humans might behave in a widespread rollout. Humans always react differently to new things. So a new EV driver will charge the battery way more often than an experienced user and not be brave enough to go as far from a charge spot. This means all the tests that engineers need to do on use, batteries etc., show a false interaction for the first while.

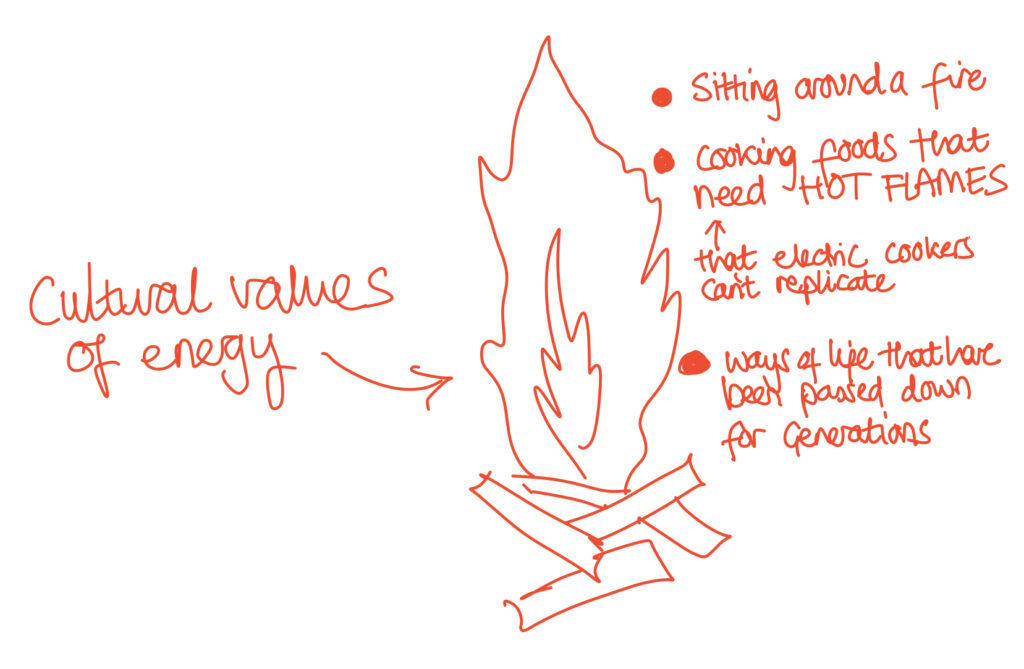

Energy also has an, often overlooked, cultural value

Human cultural values have a great significance in design. A huge number of people worldwide cook on wood fires, which are terrible for health and lungs. Even though each fire is small, it contributes a lot of carbon dioxide emissions proportionally to other lifestyle habits in un-electrified or not super strongly electrified communities when all added together. Often fires for cooking are a cultural practice; they’re something to sit around. In many cultures, there is also a spiritual significance to the light they bring.

Communities and attitudes to ownership also creates an interesting dynamic. In a study in Papua new guinea, the installation of solar panels was vehemently opposed because it significant individual ownership by being placed on the roof of a house rather than shared community ownership, which is what that community value.

Then there’s also a socio-cultural attitude to nuclear power that creates a significant barrier to decarbonisation because no matter how useful the technology might be, there are some technologies that won’t work because of cultural perceptions of safety even if the safety statistics are way smaller than the potential risk of the effect of climate change.

Decision makers are distant which causes distrust

A large amount of distrust forms because decision-makers are often so far removed from the communities they serve. This works within countries where decision-makers might sit in the capital and see less of life in remote locations or across the world. Where spaces like the UN are dominated by the US, Europe, China and India, when many effects of global warming are already being felt are experiences in drought in sub-Saharan Africa. OR in sea levels rise on small island states.

This leads to distrust, and for a world that is adapting to change, we need strong and trusted institutions to bring through constructive change. Distrust is one of the human and social barriers to decarbonization.

There are big risks of social exclusions

When we offer energy savings from home insulations or schemes to get funding for rooftop solar panels, we only give monetary incentives to those who already own property. When more of the population switch to electric vehicles, driving will be cheaper, possibly meaning those without cars are left with more expensive, less frequent public transport.

Even now, older members of the population can’t access the cheapest energy packages without going online, which is socially excluded due to no internet connection or smartphone.

Artificial intelligence makes unacceptable social calls

An excellent example of this is in self-driving cars, known as autonomous vehicles. They work by constantly learning through everyday life. The way the systems work is inherently biased towards supporting the cases for which there is more information. So, frankly, the chance of an electric car recognising a person is higher for a regular person walking to work in a suit than a person dressed as a chicken, because over its lifetime the car will see and learn how to recognise more people dressed in suits. This is very dangerous, though, because it means they are inherently rigged to understand minority groups less well. This essentially means racist cars.

Although, once we’re aware of these things, we can make some effort to counteract them. There might be other cases we aren’t able to anticipate, where technology makes calls that are entirely unacceptable by social standards and therefore cause social barriers to decarbonisation.

Conclusions

Is this bad? This post looked at human and social barriers to decarbonization. Are these bad? Are there solutions?

When we think about climate change mitigation, many people think of big goal set by the UN such as net zero and global carbon emission targets. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions is interesting; it is a global problem, and at the same time it affect all of our lives, and is inherently local. The way to transition our energy systems to low CO2 alternatives, has to wok in line with how people live. There is no way to solve the decarbonization problem with big global decisions and targets; without hitting some human social barriers. These are what this post was about. To design renewable energy systems of the future is to include human behaviour into design planning.

You may enjoy these similar posts: