This post looks at how we value healthcare. It explores whether healthcare can run in the free market, how the value of health and of life is assessed and how much responsibility an individual has for their health vs how much of that responsibility belongs to the state or society.

Every country has some sort of public healthcare and some sort of private healthcare provision. Whether payment is from an individual person (as insurance) or from the government, the system is usually large scale. That’s because it’s so much more cost effective to poole resources together. An individual wouldn’t want to own and pay for every single piece of machinery and expertise that you’d find in a hospital… It’s far more cost effective to deliver a wide scale service.

Each society makes their own system for how to share the responsibility of personal health. For example should someone who smokes a pack a day be allocated money for lung cancer treatment? If it were cheaper, could society offer smoking addiction therapy instead of lung cancer treatment? What about poor diet/obesity/alcoholism?

How does a society decide what sort of healthcare is worth providing. How do they decide an individual persons responsibility for their own heath compared with what the society can cover?

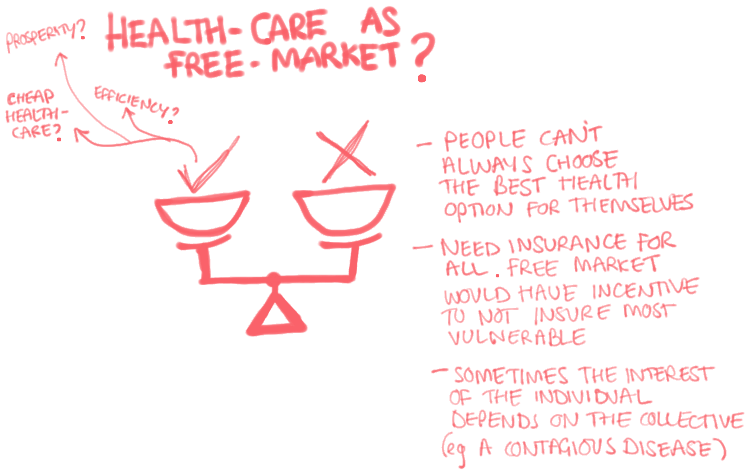

Can healthcare operate in the free market?

Even in societies that place high value on individual freedoms and support free markets with little intervention from the state, people generally accept more intervention from the government on the issue of healthcare. At least, more intervention than they might accept for decisions in business or social securities.

There are a number of reasons why healthcare doesn’t quite work in a free market sense in the same way. The free market approach assumes people will always pick the best option. This means all non-best options will get no customers and be filtered out leaving a super efficient/productive market-space. With health provision though, people don’t often know the best option for themselves so this ability to decide is murky. Then there’s the problem of insurance. There often needs to be some sort of regulation so that insurance companies are made to cover the heavy smokers/people pre-disposed genetically to cancer or obesity or diabetes. Insurers, in a totally unregulated space, might exclude high risk people from their cover. That’s how insurance works, they loose money when they have to pay out when people are ill.

There are also bigger things that make government involvement more necessary- for example contagious diseases such as the pandemic we have just been through. To prevent spread of a contagious disease governments need all of society to work together to protect those most vulnerable.

How do we assess what is worth spending on?

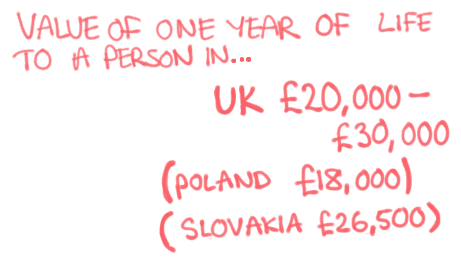

We use a metric called a QUALY to assess the benefit of health spending. It stands for ‘quality assisted life year’. In other words it’s the value of one extra year of good health. How much is one extra year of good health worth? It’s different in different societies (how weird is that as a concept in itself?!).

In the UK its £20,000 – £30,000 to the society. Of course it may be infinite to an individual or to their families and it’s so weird to put a blanket number on that. But there needs to be a baseline so that a government can make a decision like this:

If a cancer drug costs £500,000, a child who receives it and regains full health might live another 80 years (80 x £20,000 = £1,600,000) in which case the drug is good value for money for society.

In Poland the value is 18,000 euros. In Slovakia its £26,500.

Where do these numbers come from? Sometimes they’re a bit secretive because governments don’t want drug companies to lobby them accordingly is there’s a hard number. The WHO (World Health Organisation) suggests the QUALY should be in line with per capita income of a country. Treatments costing 1-3x per capita income are good value. Anything larger is not.

How should healthcare be rationed across generations?

Issues of how healthcare should be distributed between the young and old is hard to reckon with. One strategy that is often used is that an allocation of healthcare is loosely attributed to a person and rationed across their lifetime. There is a loose concept of a ration per person and it’s expected that there might be minor costs throughout a persons life but that the majority will be spent in old age.

Personal vs collective responsibility for healthcare

Benjamin Franklin “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure”

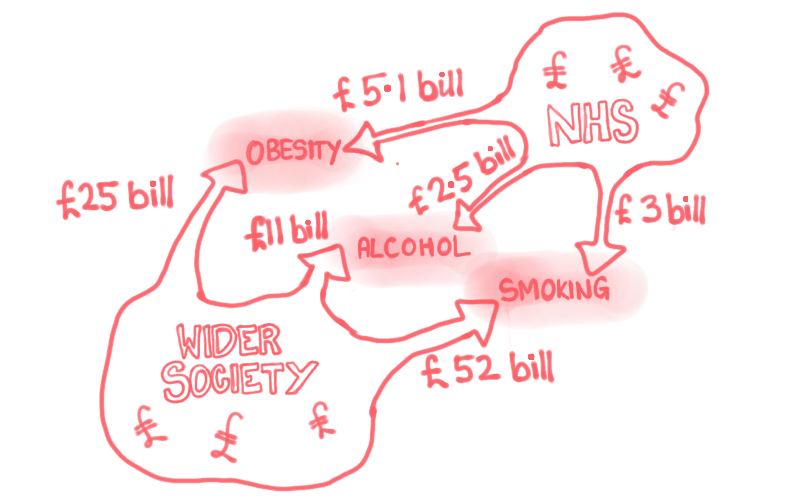

There are far fewer infectious diseases killing people in developed country nowadays. Instead, the biggest killers are cancer, heart disease, lung disease and diabetes. These diseases are highly linked to lifestyle choices such as smoking or unhealthy eating.

The costs to the NHS and society from these things, when you look at all the implications are huge. I don’t want to just list stats on this site because I fully know stats can be used to make a lot of points, but it does paint a good picture of the scenario. In the picture below I’m showing the cost to the NHS and to wider society of obesity, alcohol and smoking.

So should individuals hold any of the responsibility for that?

Its is any part on them or are their lifestyle choices their own and up for society to foot the bill for. If we think putting and responsibility on them we might have to draw boundary lines around other behaviors. Is riding a motorcycle unjustifiably risky to be covered by society? How about sunbathing?

There is also a question of how much in control of these factors a person is. If they’ve grown up around smokers and are addicted to smoking from a young age, how much free-will in giving up do they really have. Someone who can afford books/hypnosis tapes or a therapist will have more opportunity to control the habit than someone who can’t. In this book about our social contract, Minouche Shafik makes the point that to someone who has grown up addicted to cigarettes, bombarded by adverts for junk food and in a community with no recreation or no access to healthy/fresh food… how much freedom to choose their lifestyle choices do they ever really have?

Without putting the responsibility on the individual, what could be done to reduce these costs?

The first and very simple, effective way is to tax the products that you want to dis-incentivise. She gives one example of as tudy that looks at what would happened if across the world taxes were changed which increased the price of alcohol tabacco and sugary drinks by 50%. They found that over 50 years more than 500 premature deaths would be avoided and on top of that $2 trillion dollars of additional revenue would be brought in. Now thinking of the value of each healthy year of the persons like that lasts longer as a result of the different lifestyle.

Healthcare vs other societal factors

There is a problem though; we can’t really speak about these changes to lifestyle and health fairly without assessing a huge correlation in health and lifestyle- that of low income. In all countries across the world rich people live longer, healthier lives than the poor. The reason for this is a whole range of factors that aren’t even directly related to healthcare provision. Rich people have opportunities for proper nourishment as a child, education that leads to better jobs, more money for good quality food, less manual labour, less obligation to work two logs and therefore less stress on the body, fewer financial struggles which create a huge burden on mental health. All these factors can be addressed by social factors in our societies.

For example, if all children were provided high quality food three times a day at school, what might the impact be on the healthcare system when they reach adulthood. If everyone was given a good enough wage to cover their life costs, what would the impact of the mental health benefits to the people be on the healthcare system.

Thanks for reading this post about how we value healthcare!

If you enjoyed this post on society and healthcare you might also enjoy these posts: