In this post I’m going to explain as simply as I can what Quantitative Easing is. It took me a while of hearing about this on the news to delve in and get to grips with exactly what it means. Now I get it! and I want to share that with you. Whether you learn by picture or analogy- I’ve got content or relevant link for you here!

What is Quantitative Easing?

Quantitative easing is an action the bank of England can take to reboot the economy when it is in serious need. When economies crash, governments need to borrow lots of money to spend strategically to reboot the economy. QE is a specific type of borrowing where the Bank of England allow the government to borrow all the money directly from them. This makes the process immediate and gives the government flexibility to borrow a lot more money than they might in the financial market. But there are some big consequences for this type of action which we’ll explore here!

The rest of the post explores:

- Why QE is good

- Why QE is bad

- When does the government need QE

- How QE actually works

- QE in the UK: what happened?

- My QE analogy!

Why is Quantitative easing good?

Quantitative easing is good because for the economy to work money needs to flow. When there is a shock or a crisis in the economy, the flow of money stops. People stop spending and lending because they want to hold on to what they have. This prevents people from earning which reduces the amount people are able to spend even more. Having money do distribute in hard economic times literally saves lives. It’s a quick and cheap way to get that money out to the people. It doesn’t involve risks of high interest payments for year and years to come.

It’s good for developed countries to do because the consequences aren’t so bad- every country does it to some extent when they need it. Economies work in complex financial systems. They interact with deals and trades that all take place within huge amounts of debt. The amount of debt a country has is not the only factor in the strength of it’s economy; some of the worlds strongest economies have super high debt.

Why is quantitative easing bad?

Quantitative easing can be bad as it messes with the value of money which- if done irresponsibly can give a country a bad reputation. Having the central bank buy up all the bonds is like creating a fake demand. Imagine a business who have great sales figures, but 90% of their sales have been to the business owners dad. That’s not trustworthy- a business like that will not have a good reputation. There will not be a queue of people waiting to investing in their debt for profit.

Messing with the value of money (by randomly ‘creating more’ of it) is associated with unstable economies. It’s not something a country with a good reputation wants to be caught doing.

Lets explore the bad sides of QE a bit more…

The first part of QE is the borrowing bit and that is good because it enables money to flow when it’s desperately needed. But after borrowing comes the payback. The reason general borrowing can be risky is because you can get very high interest repayments. These high repayments mean a high cost to the borrowing. This is what makes borrowing possible in the first place- there has to be someone who stands to gain financially from lending the money. This is seen as a fair and square deal.

The difference between regular borrowing and QE is that the government don’t have to repay the Bank of England with any urgency and the Bank of England doesn’t charge them interest (or it allows them to waive the interest they do charge). Often the money stays in the governments hands until the agreement has expired and then the debt is just quietly written off.

This arranged buying and quiet writing off of debt is the shady part. Strong economies never want to look like they’re ‘monetising public debt’ (printing free money to cover themselves). Monetizing public debt is something that a government in desperation might do. It would make them seem untrustworthy on the world stage. Why? Because the value of money is based off the ‘market’ value of money which means…what would someone (or some institution) pay for it. QE artificially assigns a value to an amount of pounds or dollars. In other words the Banks an the government make a deal on who will pay what for what, so as some of these vouchers creep into private hands over time they do mess up the system.

Countries want to come across as financially sound and as a great investment opportunity all the time, even in financially tricky situations. Having that trustworthiness gets you better rates and more ability to borrow money and general respect on the world trading floor.

When does the government need Quantitative easing?

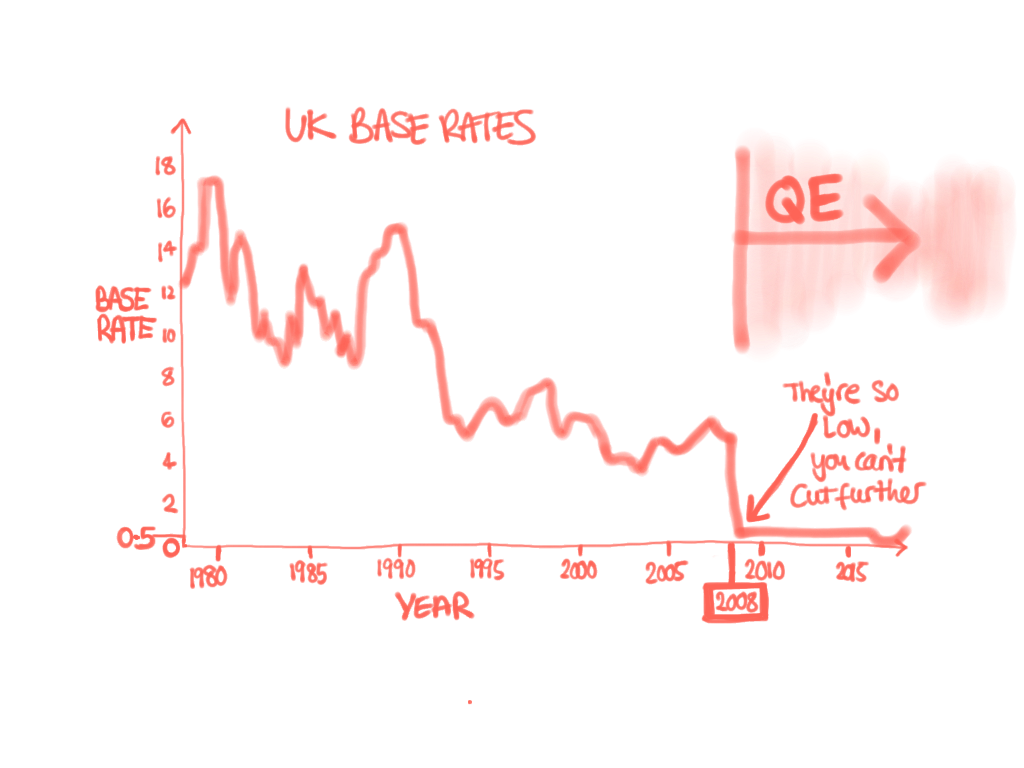

In its general operation, Bank of England influences the interest rates to change the cost of money. This either incentivises spending (boosting the economy) or incentivises saving instead of spending (which slows the economy). The bank usually influences these interest rates by prescribing them, but if they need to, they can buy or sell government bonds to either drive up demand and asset price or drive down demand and asset price. (here’s another post explaining that in more detail!)

How does Quantitative Easing work?

Since 2009 however, when interest rates had to be cut so low, there’s not much lower they can go to give the economy any further boost. There is no more interest rate buffer available to help. So, that is where extra measures, such as quantitative easing come in. The simple version of this is that the government ‘borrow’ loads of money and invest it strategically to boost economic activity.

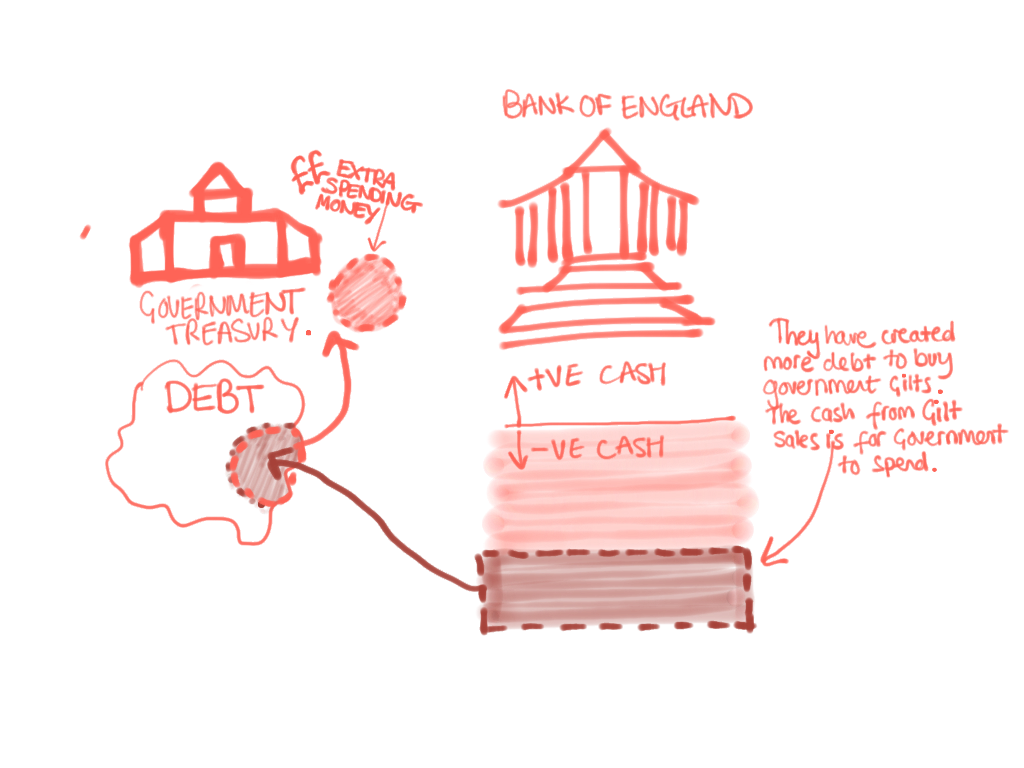

The government issue a large amount of bonds. The Bank of England ‘create’ money by putting themselves into ‘imaginary’ debt and use this debt to buy up (most of) those government bonds. They do this with a vague promise that they will, eventually, sell them all into the private sector.

What does ‘issue bonds’ mean? Basically they are selling little money vouchers. The thing is, they’re selling vouchers for money that doesn’t actually exist. They’re effectively gone into debt to create these vouchers which is why you might hear people say they are selling off parts of their debt.

Quantitative easing in the UK: what happened?

For global economic authority, power and independence you need to show trustworthiness. Having the Bank of England buy up for the £264 billion debt that the government issued in 2020 (for the Coronavirus pandemic) was only possible on the quiet promise that eventually these Gilts would be sold back to the private sector.

Since march 2009, when Interest rates had just been cut to 0.5%, £745billion was created through QE. This meant the Government sold the majority of £745 billion worth of new gilts it issued to the Bank of England. The Bank of England bought the gilts using money they had materialised for that purpose. All this was on the promise that the gilts would eventually be sold on to the private sector. From the ‘this is money’ website reporting off the Mail on Sunday, it seems that £100billion of this ran to maturity before being sold back to investors.

What does ‘ran to maturity’ mean? the treasury (the government) had to pay back the value of the bond (At face value- no interest) to the Bank of England. The Bank of England (rather than keep the money as a normal investor would) gave it back to the treasury. The same site also says that £57billion of the interest that has been earned by the Bank of England on the government Bonds over this time was also returned to the Treasury (government). All that happened is the two institutions passed money between them and somehow there was suddenly a lot more of it in existence.(https://www.thisismoney.co.uk/money/news/article-8801909/Free-money-Bank-England-150bn-UK-debt-disappear.html)

SO they basically did ‘print’ or ‘monetise’ that money. It was just a bit of a shady deal.

My Analogy of Quantitative easing

An analogy of selling debt (ie the government issuing gilts)

Imagine you buy a house and get a £100,000 mortgage approved by the bank. Then imagine a year later you want to re-do your kitchen for £10,000. You don’t have this money so you’re getting another -£10,000 on top of the -£100,000 already on your personal balance sheet (-£110,000). Normally you’d get a bank loan for the extra money. If for some reason you’re not eligible for a bank loan, imagine asking 10 of your family or friends if they’d like buy a £1,000 stake in your kitchen debt. In exchange they’d get for a promise that you’ll pay them a generous monthly sum (the interest) and after 5 years will pay them the money £1000 investment back any time they ask. If they never ask for it back, they’ll keep getting your monthly payments forever- like a little bit of extra income each month.

Why is trustworthiness so important by analogy

Think back to the house example earlier. So long as your friends want to buy into your debt because they don’t need the £1,000 immediately and like the sound of monthly payments for it instead of having it just sit somewhere in a bank, it’s a fair and square deal. If you’re the type of person who always gets fired from their job and has a gambling problem for example, your friends may not trust your promise of payments and may not want to make that deal with you- buying part of your debt is not valuable to them because they don’t trust that they will get a return. You might gamble their money away and never make the monthly payments. No kitchen for you.

A good level of perceived trustworthiness means you could renovate as many rooms of the house as you like because there will always be a demand for your debt.

Could you use quantitative easing on your house and retain trustworthiness? how would it look?

Imagine your friends are ok to buy a few hundred pounds of your debt but nowhere near the £10,000. Your gran steps in to help and slips you a cheque. She says that in time she’ll convince her friends to buy some of them so they will become a fair and square deal. She’s just helping you out for now with a ‘quantitative easing style’ deal.

Your gran is the Bank of England. coming in to save the day but promising to restore order eventually. The thing is, your gran doesn’t care about the interest payment return she’ll get for your kitchen debt. She is financially sound and just wants you to be happy and have a nice kitchen. And so, she might sell one or two of the £1,000 shares to friends. But she might also give you one or two back, once you’re on your feet. And for the ones she’s still holding…maybe she doesn’t demand full interest payments. Have you retained trustworthiness in this deal? It looks to the outside world like there is interest in your debt because some of the shares did get sold to your grand friends. But some is also quietly gifted and that bit has been monetised, in a soft way.

Is Quantitative Easing worth it?

The government can spend this money on investing in creating new jobs for people. They can give people money (for example via tax cuts) so they have more spending money and boost consumer spending. Governments can offer very cheap loans to businesses to give them a boost. They can offer really strong unemployment benefits and retraining to get people back into work. All these things are needed to get the economy back on track, so it’s necessary. How bad is the monetising problem? If your country already has a good reputation then it’s ok, you can get away with most of this.

Hopefully this post was useful. I’d love if you got in touch by commenting below!